“Anyone who wants to thwart the establishment of a Palestinian state has to support bolstering Hamas and transferring money to Hamas… This is part of our strategy – to isolate the Palestinians in Gaza from the Palestinians in the West Bank.”

—Benjamin Netanyahu[1]

i]

At a special session on October 24, 2023 of the Security Council on the situation in Gaza-Israel following the explosive events of 10/7, the Secretary-General António Guterres opened the meeting stating the “situation in the Middle East is growing more dire by the hour. The war in Gaza is raging and risks spiralling throughout the region…. I have condemned unequivocally the horrifying and unprecedented 7 October acts of terror by Hamas in Israel. Nothing can justify the deliberate killing, injuring, and kidnapping of civilians – or the launching of rockets against civilian targets. All hostages must be treated humanely and released immediately and without conditions. I respectfully note the presence among us of members of their families.” He then continued,

Excellencies,

It is important to also recognize the attacks by Hamas did not happen in a vacuum. The Palestinian people have been subjected to 56 years of suffocating occupation. They have seen their land steadily devoured by settlements and plagued by violence; their economy stifled; their people displaced and their homes demolished. Their hopes for a political solution to their plight have been vanishing. But the grievances of the Palestinian people cannot justify the appalling attacks by Hamas. And those appalling attacks cannot justify the collective punishment of the Palestinian people.[2]

The Israeli representative at the UN, Ambassador Gilad Erdan, responded describing the Secretary-General’s remarks as “shocking.” According to the Times of Israel, Erdan followed his response by posting on “X”:

The UN Secretary-General, who shows understanding for the campaign of mass murder of children, women, and the elderly, is not fit to lead the UN. I call on him to resign immediately. There is no justification or point in talking to those who show compassion for the most terrible atrocities committed against the citizens of Israel and the Jewish people. There are simply no words.[3]

Eli Cohen, Israel’s Foreign Minister, having arrived in New York to attend sessions at the UN on the Gaza-Israel situation cancelled his meeting arranged with the Secretary-General. And Benny Gantz, minister without portfolio in the current unity government of prime minister Bibi Netanyahu, on his “X” account posted, “Dark are the days when the United Nations Secretary-General condones terror.”[4] Instead of rebuking, if not cashiering, Gilad Erdan for an unprecedented public display of undiplomatic and imprudent language in lashing out at the Secretary-General, the two ministers worsened the historically strained relationship of their country and government within the ranks of the UN by adding insults to the injury of Erdan’s outbursts, especially when they can least afford to alienate further the views of the majority of member-states in the world body.

The opinion of the UN member-states was evident three days later when on Friday, October 27, the General Assembly in an Emergency Special Session on the crisis with a two-thirds majority of members voting adopted a resolution proposed by Jordan and seconded by 45 member-states calling for an “immediate, durable and sustained humanitarian truce” between Israeli forces and Hamas militants in Gaza. The final count on the resolution was 121 in favour, 14 against, and 45 abstentions. An amendment proposed by Canada on the Jordanian resolution before the vote, which called for an unequivocal rejection and condemnation of the terrorist attacks by Hamas on 10/7 and the taking of hostages failed to reach the two-thirds majority required for its adoption. In the final vote Israel was practically left alone with the United States to vote against the resolution, while Canada and most of the EU member-states abstained.[5]

The Secretary-General is chief administrative officer of the UN and he (all secretaries-general have been until present men) is also the public face of the organization. He is primus inter pares among diplomats representing their states in the world body in New York. The General Assembly appoints the Secretary-General on the recommendation of the Security Council for a five-year term that may be renewed. His responsibilities extend beyond administrative duties of the secretariat to perform additional duties entrusted to him by the Council, the Assembly, and other functional organs of the UN. In addition he is empowered by article 99 of the Charter to “bring to the attention of the Security Council any matter which in his opinion may threaten the maintenance of international peace and security”.

The remarks of António Guterres was, as is the norm of his office, carefully considered given the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In recalling for the Council that events of October 7, regardless of how outrageous and despicable they were and even as he condemned them unequivocally, have a context that need to be considered and kept in mind when calling for an immediate truce for humanitarian relief for all affected by the events while also considering the urgency of securing a more permanent settlement of the long festering conflict. The outbursts of Gilad Erdan, accompanied by the responses of Eli Cohen and Benny Gantz, reminded me of the scene from Shakespeare’s Hamlet of the outburst of Claudius, King of Denmark and brother of the late King Hamlet, driven to rage when watching the play within the play, as anticipated by Prince Hamlet, “The play’s the thing / Wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the King.” The outburst of Israel’s UN representative along with the conduct of his ministers unmasked the role of Israeli authorities that is no longer hidden, nor can be denied or deflected by invoking the terrorism of Hamas as the sole cause for the unfolding tragedy of Palestinians in Gaza.

Any event, big or small, in the life of individuals, peoples, and nations is prefixed by prehistory. Guterres’s observation that “attacks by Hamas did not happen in a vacuum”, given the continuing “56 years of suffocating occupation” Palestinians have been suffering since the June 1967 war, underscores the prehistory of October 7. It is also an indirect admission by Guterres of the dereliction of duty by the Council in not enforcing its resolution 242 of November 1967, which was renewed by resolution 2334 of December 2016,[6] for these many years knowing full well that the territories gained by Israel in the June war and inadmissibly held since make for the “suffocating occupation” of Palestinians, breeds their resistance, escalates Israeli repression, and the cycle of violence grows more acute, more horrific, and make the occupied territories a powder keg that unless defused – even if it requires direct intervention by the UN under the provisions of Chapter VII of the Charter, or by the Assembly invoking “Uniting for peace” resolution 377 (V) of 3 November 1950[7] – will inevitably explode into a wider regional war of predictable consequences with the potential of a nuclear catastrophe.

Here we might note what turned out to be Bertrand Russell’s last statement dated January 31, 1970, sent as a message addressed to an International Conference of Parliamentarians meeting in Cairo, Egypt. It was read to the gathering on February 3, the day after his death. The entire message needs to be recalled, for its relevance is as fresh and urgent in the context of the events of October 7 as it was when written, but here are a few quotes taken from it:

For over 20 years Israel has expanded by force of arms. After every stage in this expansion Israel has appealed to “reason” and has suggested “negotiations”. This is the traditional role of the imperial power, because it wishes to consolidate with the least difficulty what it has already taken by violence. Every new conquest becomes the new basis of the proposed negotiation from strength, which ignores the injustice of the previous aggression. The aggression committed by Israel must be condemned, not only because no state has the right to annexe foreign territory, but because every expansion is an experiment to discover how much more aggression the world will tolerate.

The refugees who surround Palestine in their hundreds of thousands were described recently by the Washington journalist I.F. Stone as “the moral millstone around the neck of world Jewry.” … The tragedy of the people of Palestine is that their country was “given” by a foreign Power to another people for the creation of a new State. The result was that many hundreds of thousands of innocent people were made permanently homeless.

We are frequently told that we must sympathize with Israel because of the suffering of the Jews in Europe at the hands of the Nazis. I see in this suggestion no reason to perpetuate any suffering. What Israel is doing today cannot be condoned, and to invoke the horrors of the past to justify those of the present is gross hypocrisy…

All who want to see an end to bloodshed in the Middle East must ensure that any settlement does not contain the seeds of future conflict. Justice requires that the first step towards a settlement must be an Israeli withdrawal from all the territories occupied in June, 1967 (emphasis added).[8]

Apart from being one of the greatest logicians of the last century, Russell (1872-1970) was a towering intellect and member of the House of Lords, philosopher, historian, a man of letters awarded Nobel Prize for literature, a scion of English nobility, grandson of a prime minister, Lord John Russell, sentenced to prison in 1916 for opposing the war as a pacifist, and holder of the Order of Merit. But, more importantly, in the context of his last statement in a long and distinguished life, Russell was a younger contemporary of Theodore Herzl (1860-1904) considered the founding father of Israel, and had followed the trajectory of Herzl’s imaginings brought to life as a European “colonial-settler” state by the machinations of Britain when the age of European imperialism had ended.

Russell’s last statement was prescient in implicitly warning that continued occupation of territories acquired in the June 1967 war would result not only in condemnation of Israel violating the rights of Palestinians, but also place the UN in an untenable position as when dealing with the apartheid regime of South Africa. In November 1975 the Assembly with a majority vote adopted resolution 3379 that “zionism is a form of racism and racial discrimination”,[9] and though sixteen years later in December 1991 the Assembly by resolution 86 revoked the earlier resolution on “zionism”, the worsening situation in occupied territories have led human rights organizations, such as Amnesty International and B’Tselem (Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in Occupied Territories), in their annual reports to repeatedly indict Israel’s treatment of Palestinians and violations of their rights under occupation as apartheid,[10] which is a flagrant violation of the purposes and principles of the UN Charter.

ii]

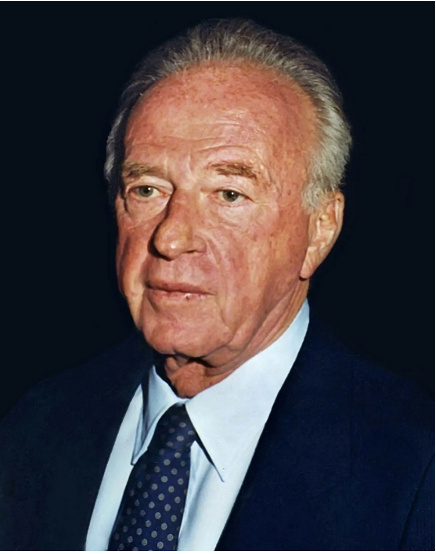

Twenty-eight years ago on November 4, 1995, Yitzhak Rabin, the prime minister of Israel and former Chief of Staff of the IDF, was assassinated by Yigal Amir, an ultra-right Orthodox Haredi Jew, for signing the Oslo Accords with the Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, Chairman of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), two years earlier in September 1993. The murder of Rabin ended the promise of the Oslo Accords of returning the territories under Israeli occupation since June 1967 and a final settlement with Palestinians in accordance with the UN’s formula of two-states – an Arab state and a Jewish state – in the Mandate of Palestine adopted in the General Assembly resolution 181 of November 29, 1947.[11]

The return of Rabin to power in the June 1992 election was greeted with relief by friends and adversaries of Israel in the region and beyond. His return ended the run of Likud party in power for all but two of the past fifteen years. The June election was hard fought, but ahead of it Rabin had to win the leadership of the Labour party in the primary, first in Israel’s history, against Shimon Peres and two other candidates held in February. Rabin emerged as the leader and the political strategists in the party quickly recognized that their greatest electoral asset was Yitzhak Rabin himself, a proven realist and pragmatic military commander at the head of the IDF during June 1967 war, an experienced diplomat, and a straight-talking politician with a proven record on security issues as Defence Minister.

The previous decade had begun with Prime Minister Menachem Begin and his Defence Minister Ariel Sharon launching the Lebanese war in June 1982 against the PLO based in Lebanon for the attempted assassination of the Israeli ambassador Shlomo Argov in London by members of a renegade Palestinian faction led by Abu Nidal.[12] The Israeli invasion of Lebanon culminated with the encirclement of Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatilla in Beirut and massacres of men, women and children by the Phalangists, a Christian militia, allied with the IDF in September. The aftermath of this grissly killings led to judicial inquiry by the Kahan commission, chaired by the president of the Supreme Court, Justice Yitzhak Kahan, which found Sharon indirectly responsible for the massacres and recommended his dismissal. Sharon was forced to resign, and Begin incapacitated by a severe depression resigned with Yitzhak Shamir replacing him as the prime minister. The Lebanese fiasco was followed by the First Intifada (general uprising) in the occupied territories beginning in December 1987 and ending with the signing of the Oslo Accords. Rabin as Defence Minister during this period was responsible in containing and putting down the uprising with use of force. Taken by surprise, Rabin learned that while force might contain and suppress the uprising but, according to his biographer Itamar Rabinovich, he was quoted saying “the solution can only be a political one.”[13] This was an inkling of Rabin being a security hawk and a political dove. Rabinovich also cites another episode from early 1974 when Rabin was first elected as a Labour party member of the Knesset and given the Labour portfolio by Prime Minister Golda Meir. Israelis were still stricken from the shock of the Yom Kippur war of October 1973 when Rabin as a junior minister engaged in speaking with people in informal meetings and one such meeting was reported in the press. Rabinovich narrates,

Meir was not happy either with Rabin’s statement to a group of young Orthodox Zionists that was leaked to the Israeli press on April 23: “I am guided by an important principle—the people of Israel must know that in order to achieve peace among nations contact must be established that would lead to a political settlement. On Jerusalem I will not compromise; that is my focal point.” He was then asked by National Religious Party (NRP) Minister Michael Hazani, “And Ramallah?” He answered, “That is not a question of life and death for me.” A settler from Etzion Bloc asked, “And what about me?,” to which Rabin responded, “It won’t be terrible if we go to Kfar Etzion with a visa.” A girl in the audience then asked, “And what about all of the historical Land of Israel?” to which Rabin answered, “For me the Bible is not a land registry of the Middle East. It is a book that provides education in values and its purposes are different.” This was Rabin at his bluntest. In an Israel still reeling under the effects of the October War this far-reaching statement failed to cause the uproar it would have caused under different circumstances. But too much should not be read into it. It was not a harbinger of the Oslo Accords nearly two decades later but a reflection of Rabin’s basic approach, namely, that the bulk of the West Bank must not be kept by Israel and certainly not settled by it (emphasis added).[14]

But ahead of the June 23 election day, Rabin on several occasions expressed this approach, different from Shamir and the Likud party, in negotiating peace agreement with Arab states and Palestinians. In an article for the Jerusalem Post published on June 1, Rabin stated:

I am unwilling to give up a single inch of Israel’s security, but I am willing to give up many inches of sentiments and territories—as well as 1,700,000 Arab inhabitants—for the sake of peace. That is the whole doctrine in a nutshell. We seek a territorial compromise which will bring peace and security. A lot of security.[15]

On becoming prime minister, Rabin was immediately saddled with the responsibility of the peace process initiated jointly by the United States and the Soviet Union in the Madrid conference of October 31-November 1, 1991 following the conclusion of the first Gulf War in February 1991 against Iraq for occupying Kuwait by a coalition led by the United States under UN authorization. The Madrid conference would be the last conference co-chaired by the United States and the Soviet Union that brought together all the Arab states, including Palestinian delegation as part of the Jordanian delegation, and Israel to begin negotiations for a comprehensive settlement of the Arab-Israeli conflict. The format for negotiations was set by the conference chairs called the Madrid process. There were three tracks of direct negotiations arranged: between Israel and Syria, Israel and Lebanon, and Israel and Jordanian-Palestinian joint delegation. The Palestinian delegation consisted of West Bank and Gaza residents with no direct representative of the PLO since its leadership with Arafat at its head, having wrongly gambled in supporting Saddam Hussein of Iraq during the lead up to the Gulf War, was not invited to Madrid and had to settle for a subordinate role as part of the Jordanian delegation.

Rabin was not comfortable with the Madrid process, as his preference was for Israel not to engage with Arab states in a collective setting. The Madrid process was given a pause for the Israeli election after a series of fruitless meetings held in Washington attended by the delegation sent by Likud government headed by Yitzhak Shamir in office. Rabin elected prime minister handed the Foreign Ministry to Shimon Peres with authority to engage in the Madrid process, while he kept the Defence Ministry for himself. As negotiations began following the June election, it became clear that Palestinians attached to the Jordanian delegation in Washington were receiving instructions from the PLO based in Tunis and an alternative setting, or track, needed to be arranged for direct talks between Israelis and representatives of the PLO. Ahead of the June election, Rabin in an interview with the press indicated he had no objection for a separate Palestinian delegation that eventually was formalized in what became the track-two diplomacy begun in December 1992 as the Oslo process. Eight months later the Oslo process culminated in the agreement, known as the Oslo Accords, in August 1993 between Israel and the PLO, and the formal signing ceremony held in Washington a month later on September 13 by President Clinton that brought Rabin and Arafat together at the White House. Before Rabin and Arafat

met for the first time in Washington, formal letters dated September 9, 1993, were exchanged between the PLO and Israel signed respectively by the two leaders. In the PLO letter addressed to Rabin, Arafat wrote,

The signing of the Declaration of Principles marks a new era in the history of the Middle East. In firm conviction thereof, I would like to confirm the following commitments:

The PLO recognizes the right of the State of Israel to exist in peace and security.

The PLO accepts United Nations Security Council Resolution 242 and 338.

… The PLO considers that the signing of the Declaration of Principles constitutes a historic event, inaugurating a new epoch of peaceful coexistence, free from violence and all other acts which endanger peace and stability. Accordingly, the PLO renounces the use of terrorism and other acts of violence and will assume responsibility over all PLO elements and personnel in order to assure their compliance, prevent violations and discipline violators.

In view of the promise of a new era and the signing of the Declaration of Principles and based on Palestinian acceptance of Security Council Resolutions 242 and 338, the PLO affirms that those articles of the Palestinian Covenant which deny Israel’s right to exist, and the provisions of the Covenant which are inconsistent with the commitments of this letter, are now inoperative and no longer valid. Consequently, the PLO undertakes to submit to the Palestinian National Council for formal approval the necessary changes in regard to the Palestinian Covenant.

Rabin replied,

In response to your letter of 9 September 1993, I wish to confirm to you that, in light of the PLO commitments included in your letter, the Government of Israel has decided to recognize the PLO as representative of the Palestinian people and commence negotiations with the PLO within the Middle East peace process.[16]

The Oslo Accords comprised a Declaration of Principles (DoP), a memorandum clarifying some points in the main document, and four appendices. The appendices dealt with election in the occupied territories, the withdrawal of Israeli forces from Gaza and Jericho, Israeli-Palestinian economic cooperation, and the regional economic development. The DoP provided the framework for the interim agreement setting up Palestinian self-rule in Gaza and Jericho and its implementation through further technical discussions to be concluded within three months of signing of the Accord. The significance of the DoP was the agreement that Palestinians were to be given a full measure of autonomy and that Israel would bring to an end its military occupation. The Oslo Accords were in effect confidence-and-security building measures within a fixed time frame of five years with negotiations starting no later than the end of 1995 on a list of issues, such as the status of Jerusalem, the Jewish settlements in the occupied territories, demarcation of borders and issues left over from previous negotiations, and at the end of which there would be negotiation to seal the final status agreement.

Rabin was in a hurry to bring an end to the Intifada, reach an agreement with the PLO leadership giving Palestinians autonomy in the occupied territories administered by their own elected representatives with policing powers and thereby relieving Israelis of that onerous responsibility, and build trust between Israel and Palestinian Authority before concluding the final status agreement for a meaningful future in terms of peaceful coexistence for both people. But there was also the need to hurry the process if it was not to be derailed by those forces seeded in the territories during the years of occupation since June 1967. The Intifada began in December 1987 marking the twentieth anniversary of the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, and in these two decades the new political phenomenon of religious fanaticism in the territories was bent upon shutting the doors on any compromise of trading land for peace as implied in the UN security council resolution 242.

Jewish settlements in the occupied territories began to grow and spread in the period following the October war of 1973, and pushed by the settler movement Gush Emunim (the Bloc of the Faithful) had become a powerful lobby that no political party could ignore. Menachem Begin, as Likud leader with coalition partners on the religious right and elected prime minister in 1977, spoke of occupied territories as part of Eretz Israel (Land of Israel) to be settled by a new generation of Israelis making the land non-negotiable. The settler movement inevitably came into violent confrontations with Palestinian inhabitants of West Bank and Gaza, and such incidents coalesced to finally erupt in the Intifada of 1987-93.

The Palestinian uprising came from within the occupied territories surprising the PLO leadership based in Tunisia after being expelled from Lebanon during Israel’s Lebanese war. The extent and depth of Palestinian support for the uprising brought into prominence a new generation of activists connected with mosques and religious institutions and among them was “Hamas”, an acronym for the Islamic Resistance Movement founded by Ahmad Yasin, teacher and local imam (religious leader), in Gaza around the time the Intifada started. Ahmad Yasin, a paraplegic, was connected with the Muslim Brotherhood organization in the territories and Hamas was established as an off-shoot of the Brotherhood. The Intifada also became the conduit for the supporters of Hamas to organize the politics of “resistance” in terms of the Brotherhood ideology of “jihad” (holy war). Gush Emunim’s use of the terminology Eretz Israel/Land of Israel, meaning the “land” over which Jews claim “historical rights” and for them to redeem and settle, was countered in the Hamas Charter that all of Palestine is Islamic Waqf (religious endowment) “consecrated for future Muslim generations until Judgment Day” and, hence, cannot be despoiled, squandered, given or taken away from Muslims by anyone. As Hamas gained popularity it posed a threat to secular nationalist appeal of the PLO, a threat that its enemies among Arab states in the region, including Israel, would exploit to create divisions among Palestinians. Israeli intelligence agencies, Mossad and Shin Bet, would have been negligent in failing to penetrate Hamas with informers and goad Hamas activists escalate the rhetoric of religious extremism and terrorist violence to out-flank the PLO from the right.[17]

Rabin had failed during his time as Defence Minister to impede the settler movement in the territories that came to haunt him as prime minister. After signing the Oslo Accords Rabin was a marked man, his death foretold. The Intifada had taken the lid off domestic terrorism. Gush Emunim and the ultra-religious right in Israel had found in Hamas their partner in the zero-sum dance of mutual hate and violence. Within six months of signing of the Oslo Accords the ring of fire was ablaze. In Hebron in the West Bank the ultra-right terror of the settler movement exploded on a cold February morning. Here is Robert Slater’s account in his biography of Rabin:

At 5.20 am on 25 February, 1994, some 700 Palestinian Arab men, women and children, having awoken and risen in the dark and eaten a quick breakfast, swarmed into the mosque in Hebron for dawn prayers that marked the start of the fast—observed from sunrise to sunset—on each of the 30 days of Ramadan. Prayers had just started. Worshippers were kneeling forward on plastic mats, touching foreheads reverently to the floor. While they were praying, Baruch Goldstein, a Jewish settler from the nearby community of Kiryat Arba arrived on the scene. He was a physician and a well known activist. A year earlier he had prophesied in a synagogue that ‘there will come a day when a Jew will get up and kill many Arabs for killing Meir Kahane’ (the Jewish zealot slain in New York City in 1990). Right-wing Jews said many extreme things, and Goldstein’s words seemed to be wild rhetoric, but nothing more.

As the worshippers continued their prayers, Goldstein silently approached the mosque. He wore a reserve captain’s olive-green army uniform and a yarmulke on his head and he carried a military-issue Galil assault rifle. Speaking in Arabic, he asked a Palestinian guard at the door to let him enter, but the guard tried to keep him from going in, arguing that Israelis were forbidden to step inside during Moslem prayers. Goldstein angrily persisted: ‘I am the officer in charge here, and I must go in.’ Knocking the guard down with his rifle butt, he rushed inside, positioning himself close to the backs of the worshippers in the rear row.

Then, saying nothing, he opened fire. Seven people died immediately, all shot in the head. Others ran for cover, screaming, calling for help. Goldstein kept up the barrage of bullets for another ten minutes. In the end, he killed 30 Palestinians. He had been hoping to kill the peace process as well by raising the temperature of the Arab-Israeli conflict to such heights that talking peace would have been impossible. He succeeded, but only temporarily. In their grief and fury, Palestinians were in no mood to talk about implementing the DoP. Now it was not just Hamas terror that was threatening to blow up the Oslo accord, it was Israeli terror as well.[18]

Few weeks later on April 6 and 13 Hamas fighters struck with deadly violence carried out by suicide bombers in two Israeli towns, Afula and Hadera. Newton’s third law of motion had been activated and since violence is addictive, the law of karma, of cause and effect, as mentioned in Hindu scriptures, would run its course until the greater moral law of repentance, mercy, and forgiveness brought an end to the cycle of the primitive law of an eye for an eye. The signing of the Oslo Accords, despite their limitation given the asymmetry in power relationship between Israel and the PLO, was a heroic effort on the part of Rabin and Arafat to break the cycle of enmity between their two people and venture forth in the path of reconciliation for a better future together for Israelis and Palestinians.

The opposition to Rabin’s government in the Knesset was led by Benjamin Netanyahu elected to replace Yitzhak Shamir as Likud’s leader following the June 1992 election. Netanyahu led Likud to join a broad coalition that spanned the right wing spectrum of Israeli politics against the Oslo Accords. This coalition was spear-headed by the Yesha Council, the organization of West Bank and Gaza settlers and anchored by hardliners in Gush Emunim. For this coalition of right wing activists, settlers, and opposition politicians the Oslo Accords loomed as the most serious threat to their objective of turning the occupied territories into an integral part of Eretz Israel, and they were determined to obstruct and deny any compromise solution for peace with Palestinians. The opposition’s tactics to derail Oslo Accords, according to Itamar Rabinovich, “unfolded in several stages: legitimate political opposition; illegitimate political opposition; discrediting and delegitimizing the government and its leader; dehumanization of the political rival; symbolic conduct and ritual murder; violent political conduct and actual assassination.”[19]

Rabin’s government was branded by the opposition coalition Judenrat, the deadly smear against Jews who collaborated with the Nazis. Ariel Sharon, nicknamed the “Butcher of Beirut” after the Kahane commission inquiry into the 1982 massacres of Palestinians in the refugee camps of Sabra and Shatilla during Israel’s Lebanese war, went public against Rabin, his former commander and mentor. Sharon accused Rabin’s government as “an insane government that shrinks Israel to Auschwitz borders, a reckless government, submissive, confused, treacherous, insane.”[20] On October 19, 1994 a Hamas suicide bombing of a bus in Tel Aviv killed twenty-two Israelis and wounded as many. Netanyahu appeared at the site of the bombing and addressing the television cameras denounced Rabin saying, “The PM chose to prefer Arafat and the welfare of Gaza’s residents at the expense of the inhabitants of Israel.” The ultra-right Jews and the settler movement went into a frenzy escalating the rhetoric against Rabin, while rabbis of the ultra-Orthodox Jews raised the stake by introducing two radical concepts into the public discourse: the “Law of the Pursuer” (Din Rodef) and the “Law of the Informer” (Din Moser). As Itamar Rabinovich explains, “Both laws were adopted from the long history of the Jews in the diaspora and under foreign rule, and both sanctioned the killing of a Jew who either pursued or prosecuted other Jews or informed on them to gentile authorities.”[21]

Rabin persisted in the path taken. A week after the Tel Aviv bombing on October 26 King Hussein of Jordan and Rabin signed the Jordanian-Israel Peace Treaty at a ceremony held north of Eilat at the border between Jordan and Israel, and was attended by President Bill Clinton accompanied with a U.S delegation. In December 1994 Rabin accompanied by Shimon Peres and joined by Arafat received the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, Norway. As the year 1995 opened the opposition to Rabin and

the Oslo Accords grew increasingly belligerent. Orthodox rabbis in the diaspora were drawn into the discourse over the “law of the pursuer” and the “law of the informer” that sanctioned the killing of a Jew in breach of either law. Some agreed, others were hesitant, and one warned against alighting a fire with such discourse. Rabbi Abraham Hecht, of Brooklyn, New York, opined “He who gives away parts of the Land of Israel, he who kills him first is rewarded, but I was not since he is still alive.” And Rabbi Kurtz, the Chabad leader in Florida, decreed that “Rabin qualifies as an enemy and therefore is subject to the rule act swiftly to kill the person who comes to kill you.”[22]

The timetable set in the Oslo Accords for the conclusion of the final status negotiations was within five years of the implementation agreement signed in May 1994. In September 1995 negotiations to expand the area in stages under Palestinian Authority (PA) within the West Bank beyond Jericho known as Oslo II was signed in Washington. The incremental handover of the West Bank territory to PA was demarcated as Areas A, B, and C, and Oslo II marked the momentum set for reaching the final status agreement. On October 5, the Knesset was scheduled to vote on Oslo II, and the opposition called for a mass rally on the same day in Zion Square in Jerusalem. The rally turned into a mob chanting “Death to Rabin.” Netanyahu as the leader of the opposition in the Knesset addressed the rally and taunted the non-Jewish character of the government relying on Arab-Israeli votes for the approval of Oslo II. Netanyahu’s taunts inflamed the anger of the crowd and he failed to admonish the rally for its objectionable conduct. Rabin’s car was mobbed near the Knesset. Fouad Ben Eliezer, Labour Minister, was assaulted by the crowd on his way to the Knesset and inside he scolded Netanyahu, telling him, “I suggest you wipe the smile off your face. Your people are crazy. If someone will be murdered, you will be responsible.”[23]

A month later on November 4, Rabin and Peres were enthusiastically greeted at a peace rally in Malchei Yisrael Square near the City Hall in Tel Aviv. Yigal Amir had been stalking Rabin since the signing of the Oslo Accords in Washington in September 1993. Amir was waiting at the rally, which drew a crowd of a hundred thousand supporters of Rabin. Here was the proof of the silent majority of Israelis warmly embracing Rabin and his peace policy.

Rabin was among his people, and both he and Peres were heartened by their genuine affection. Rabin had another private reception to attend after the rally. He took leave shortly after addressing the friendly crowd and walked behind Peres for his car. Yigal Amir waited in ambush close to the stairs that Rabin descended, and unloaded his weapon at point-blank range into the prime minister. Two of the bullets smashed into Rabin. His security detail had failed him, and by the time he was rushed to Ichilov hospital nearby Rabin was clinically dead. Shortly after 11 pm, an hour and twenty minutes after he was shot, the official announcement was made that the prime minister had died of bullet wounds fired by Yigal Amir. On the twenty-eighth anniversary of Rabin’s murder as Gaza-Israel descended into a vortex of violence, the prehistory of October 7, 2023 was written on the evening of November 4,1995 and punctuated by gun shots that killed a remarkable man for all ages, Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin of Israel, and with him died the promise of peace between Israelis and Palestinians, Arabs and Jews, that was so tantalizingly near and since that fateful evening has vanished like a mirage in the desert.

_______________

Notes:

Photos: (i) Yitzhak Rabin (1922-1995), Courtesy: Britannica; (ii) Rabin, Clinton, Arafat, Courtesy: cfr; (iii) Arafat, Peres, Rabin, (Courtesy: Nobel Prize Committee).

[1] Gidi Weitz, “Another Concept Implodes: Israel Can’t Be Managed by a Criminal Defendant,” in Haaretz.com, October 9, 2023.

[2] See Secretary-General António Guterres’s speech:

[4] Ibid.

[5] See: https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/10/1142932

[6] See: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N16/463/89/PDF/N1646389.pdf?OpenElement

[7] See: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/RESOLUTION/GEN/NR0/059/75/PDF/NR005975.pdf?OpenElement

[8] See Russell: https://www.connexions.org/CxLibrary/Docs/CX5576-RussellMidEast.htm

[9] See “zionism is racism” resolution: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/RESOLUTION/GEN/NR0/000/92/PDF/NR000092.pdf?OpenElement

[10] See the latest Amnesty International Report:

[11] See: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/RESOLUTION/GEN/NR0/038/88/PDF/NR003888.pdf?OpenElement

[12] Dan Raviv and Yossi Melman, Every Spy A Prince: The Complete History of Israel’s Intelligence Community (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990), p. 268.

[13] Itamar Rabinovich, Yitzhak Rabin: Soldier, Leader Statesman (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2017), p. 158.

[14] Ibid., p. 100.

[15] Robert Slater, Rabin of Israel: Warrior for Peace (New York: HarperPaperbacks, 1996), p. 477.

[16] See both letters with other relevant documents pertaining to the Oslo Accords in Omar Massalha, Towards the Long-Promised Peace (London: Saqi Books, 1994), p. 302. Also see Walter Laqueur and Barry Rubin, editors, The Israel-Arab Reader: A Documentary History of the Middle East Conflict, Sixth Revised Edition, (New York: Penguin Books, 2001).

[17] See Dan Raviv and Yossi Melman, op.cit., pp. 379-404. Also, Ziad Abu-Amr, Islamic Fundamentalism in the West Bank and Gaza (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1994).

[18] Robert Slate, op.cit., pp. 590-91.

[19] Rabinovich, op.cit., p. 221.

[20] Ibid., p. 224.

[21] Ibid., p. 225.

[22] Ibid., pp. 226-7.

[23] Ibid., p. 228.

Thanks Salim.

I remember Rabin's assassination and the events that preceded it - Wow, were we ever encouraged by these developments. I was very enthusiastic of Rabin's initiatives and was devastated when he was killed by a zealot, no less, with no critical thinking skills (so much so that he had to consult with a rabbi - of his opinion of course.)

I must say that your reflexion takes a long time to reach the Rabin era and in this respect, you almost lost me as a reader.

I dare say, despite my pining for Rabin-like diplomacy in the middle east, I cannot agree with your conclusion. While zealotry and mindless religious fervour (or any faith) can certainly derail processes, there is room to be a bit more optimist. The issue in my view is that those in power (supra national governing bodies as well as national governing bodies including Canada's) at this time want this chaos and indeed need it to accomplish goals. There is no will on their part for peace in that region of the world. This is apparent given the one-sided view provided by the media and the allowance of anti-fa and anti-Israel demonstrations to take place. Moreover, silence as to the way Hamas has been behaving over many years (without ever giving up on its primary objective - the anihilation of Israel and the Jews, further supports this contention.

But, I am cautiously optimistic that the upcoming US election will have a true peace seeker and maker will provide a renewal of hope in the region, as long as measures are taken in the immediate to allow for 4 years of "getting to know thy neighbour" and in the long term, to prepare the next leader to continue the work begun. That said the 2 major enemies of a lasting peace in the area (reliegious zealatry - on both sides - and chaos seeking supra governments will exist for a long time if not forever and will continuously be a cause for concern.

Looking forward to seeing you again.

Cheers.